Evaluating the relevance of greenwashing in a society where green has become a fad.

The Rise of Green Marketing

As the world continues to grapple with the urgent need for sustainable development, a disturbing trend has emerged – GREENWASHING. Companies and organisations are increasingly using deceptive marketing tactics to portray themselves as environmentally friendly, while their actual practices may be far from sustainable.

At the COP27 climate summit in Egypt last year, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said, ‘We must have zero tolerance for net-zero greenwashing. [1]

Greenwashing implies “a discrepancy between words and deeds, which combines poor environmental performance and positive communication about the environmental performance.” [4]

Consumers nowadays seek green products while investors want to invest in companies that care about the environment. [6] In the environmental era, firms are continuously looking for new ways to distinguish their products. Companies are eager to, on the green trend due to which greenwashing has become prevalent. [3]

In the domain of environmental management, the term “greenwash” is used as a metaphor akin to the term “whitewash” to create an image among consumers that a firm implements sustainable business processes and practices. [8]

Typically, businesses use marketing and promotion to “greenwash” their products by making false claims that their product is recyclable, biodegradable, and eco-friendly.[1]

Before we explore greenwashing, it’s important to understand the difference between it and genuine green marketing. Let’s take a closer look.

Greenwashing and green marketing: two sides of the same coin

There’s a thin line between green marketing and greenwashing.

Green marketing can be defined as “an ethical approach to sustainability of an organisation who adopts green practices as their major corporate social responsibility to meet the challenges put forward by consumers without having any ill-effect on the environment.”[8] Greenwashing is defined as the “act of misleading consumers regarding the environment-friendly practices of a company.” [5] Green marketing tends to increase the preference of consumers towards greener products whereas in the case of greenwashing a company deceives the consumer into believing their products are green by making exaggerated claims so that the consumer is convinced to buy the product. [10]

The seven sins of Greenwashing

An in-depth understanding of greenwashing requires us to know about the ‘seven sins of greenwashing’ [7]. The seven sins are as follows:

1. Sins of no proof – This happens when an environmental claim about a product is not supported by any relevant data or certification.

For example, Facial tissues or toilet tissue products that claim various percentages of post-consumer recycled content without providing evidence

2. Sins of vagueness – This happens when a product makes claims that need to be better formed and can be easily misunderstood by the consumers.

For example, All natural claims. Arsenic, uranium, mercury, and formaldehyde are all naturally occurring, and poisonous. All natural isn’t necessarily green.

3. Sins of hidden trade-offs – This happens when a claim about a product being green is made by looking at a limited set of characteristics while overlooking some significant environmental issues.

For example, Paper is not necessarily environmentally preferable because it comes from a sustainably harvested forest. Other environmental issues in the paper-making process, such as greenhouse gas emissions are equally important.

4. Sins of irrelevance – This happens when truthful yet unhelpful and useless information is provided to the consumer in the name of a green claim.

For example, Companies make CFC-free claims despite the fact that CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) are banned under the Montreal Protocol.

5. Sins of lesser of two evils – This is committed by making claims that are true in the product category but which may distract the consumers from other health or environmental risk. This happens when true claims about a certain product might divert consumers’ attention from the product’s other environmental effects.

For example, Organic cigarettes.

6. Sins of false labels – This is committed when a product through words or images tries to give an impression of a third-party endorsement when no such endorsement exists.

7. Sins of fibbing – This is committed by making green claims that are untrue.

For example, Products falsely claiming to be ENERGY STAR® certified or registered.

The dangers of unchecked greenwashing

The consumer is being led to feel that by adopting the practices advocated by particular companies, they are aiding the environment, even though this may not be the case. Consumers may lose faith in businesses that are doing well for society as a result of greenwashing. Consumer and investor confidence in green products and environmentally conscious businesses can be severely harmed by greenwashing, which makes these stakeholders reluctant to reward businesses for their environmental performance. Thus, the company can lose both consumers and investors while tarnishing its brand image as a result of greenwashing,[2]

Major Industries where greenwashing is rampant in India

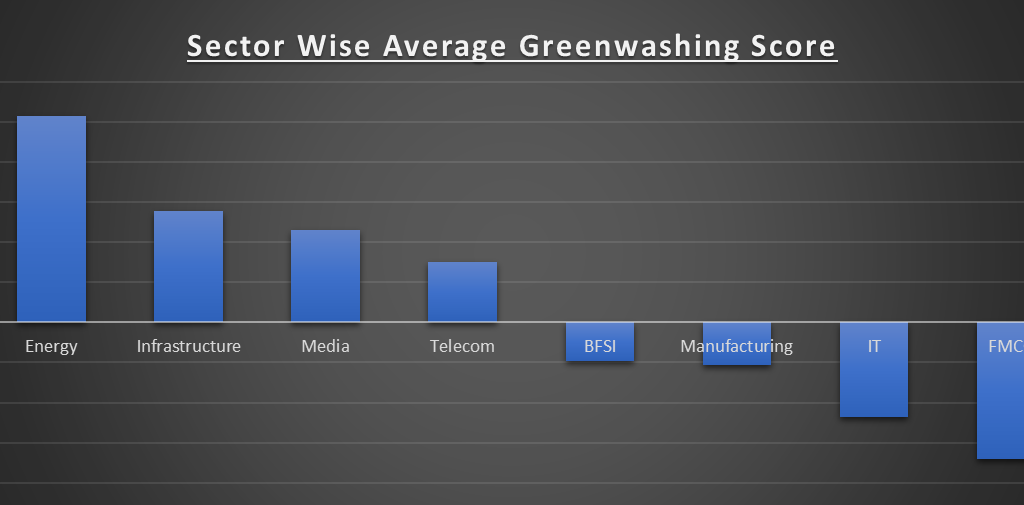

Sensharma, Sinha and Sharma,2022 try to look at ESG reporting in India through a lens of greenwashing. They take the companies listed under NIFTY STOCK 50 index from the year 2019-20 using available ESG scores. They try to measure and compare the extent to which the companies are engaging in greenwashing activities. Data for the study is collected through secondary sources like Bloomberg and Thompson Reuters.[9]

The results of the study indicate that “54% of the 48 companies which are part of the sample are greenwashers”. The average greenwashing score turned out to be the most in the case of the energy sector and the least in the FMCG sector. [9]

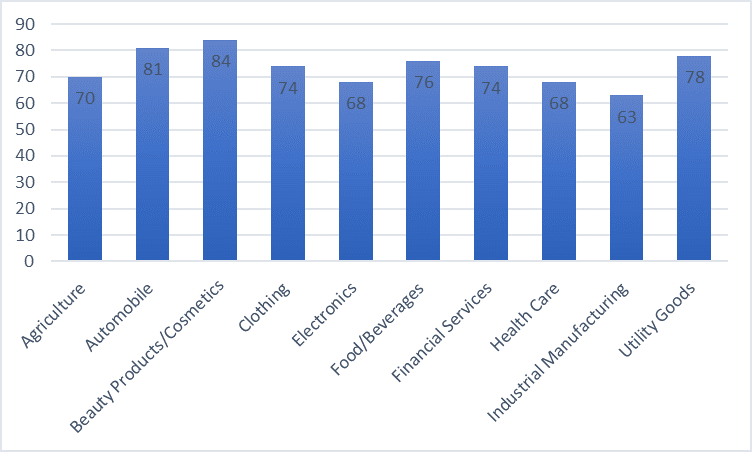

Singhal and Agrawal, 2021 have tried to understand the concept of greenwashing from a consumer point of view in the state of Rajasthan, India. They have also tried to find out which sector in India greenwashes the most. A sample size of 100 individuals was chosen for the study and 88 people responded. The research was conducted through the medium of questionnaires which were mailed to the respondents. Some secondary data was also used in the analyses. The results of the study indicated that the beauty/cosmetic industry greenwashes the most, followed by Automobile Industry. [11]

So we can see that there is a difference in the consumer perception and the actual greenwashing score of the industries. While the consumer perceives that greenwashing is rampant in the beauty products/cosmetic industry, the greenwashing score comes out to be the most in the Energy Sector in India.

Way forward

In the current scenario, greenwashing is a significant issue that requires attention.

Consumers need to be aware of this practice and should read the labels carefully while buying green products. They should also do the necessary research before purchasing a product solely because it makes green claims.

Brands need to be aware that modern consumers value authenticity. While indulging in greenwashing may help them close deals quickly, there is a chance that consumers might lose faith in the company and stop buying their products altogether.

Businesses need to take their corporate social responsibility seriously and refrain from greenwashing activities as it can tarnish their image. They need to invite customers to join them in the effort to create a future that is both inclusive and truly green.

In the quest for a sustainable future, combating greenwashing emerges as a vital step towards real progress. With the awareness of this deceptive practice, consumers now hold the power to make informed choices. By diligently scrutinizing labels and conducting thorough research, one can differentiate between authentic green products and those that merely make false claims. Likewise, brands must recognize that the modern consumer values transparency and genuineness.

Though greenwashing may yield short-term gains, the long-term consequences can be severe, eroding consumer trust and jeopardizing their market presence. Embracing corporate social responsibility becomes imperative for businesses, as they strive to build an unblemished reputation and foster a partnership with their customers. Together, by rejecting greenwashing and embracing a shared vision of inclusivity and true sustainability, we can pave the way towards a greener future for all.

If you need expert guidance on navigating the complexities of sustainability and avoiding greenwashing, reach out to our sustainability experts at Carbon Mandal and let’s work together towards a truly sustainable tomorrow.

List of references

[1] https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/10946-greenwashing.html [2] https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e2df54e3-5187-4a7f-b7fd-3db6d199e280 [3]Chen, Y.S. and Chang, C.H. 2012. “Enhance green purchase intentions: the roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. “Management Decision 50(3) :502-520. [4] Gao, H., Knight, J. G., Zhang, H., Mather, D., & Tan, L. P. 2012“Consumer scapegoating during a systemic product-harm crisis. Journal of Marketing Management” 28(11–12):1270–1290. [5] Parguel, B., Benoıˆt-Moreau, F., & Larceneux, F.2011. “How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: A closer look at ethical corporate communication.” Journal of Business Ethics 102(1):15–28. [6]Pizzetti, Marta, Lucia Gatti, and Peter Seele. 2021.”Firms talk, suppliers walk: Analysing the locus of greenwashing in the blame game and introducing ‘vicarious greenwashing’.” Journal of Business Ethics 170 (1): 21-38.https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:kap:jbuset:v:170:y:2021:i:1:d:10.1007_s10551-019-04406-2

[7]Lim, Weng Marc, Ding Hooi Ting, Victor Sudirman Bonaventure, Alan Putera Sendiawan, and Pengestu Patanmacia Tanusina. 2013. “What happens when consumers realise about green washing? A qualitative investigation.” International journal of global environmental issues 13 (1) :14-24. [8]Mukherjee, R., and I. Ghosh. 2014. “Greenwashing in India: a darker side of green marketing.” The International Journal of Business & Management 2(1 ):6-10. [9] Sensharma, Sushobhan, Manish Sinha, and Dipasha Sharma.2022. “Do Indian Firms Engage in Greenwashing? Evidence from Indian Firms.” Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 16(5): 67-88.https://ro.uow.edu.au/aabfj/vol16/iss5/5/

[10]Vijay, Praful. 2019. “The Impact of Greenwashing on Green Brand Trust from an Indian Perspective”. Asian Journal of Innovation and Policy 8(1) : 162-179. [11] Singhal,Himanshu; and Ankita Agrawal.2021. “Greenwashing : A study on consumer behaviour and effectiveness in Rajasthan.” EPRA International Journal of Environmental Economics, Commerce and Educational Management 8(2) :1-5.